The incomplete story of CompleteSet

The story of why my venture-backed startup failed and what other founders can do to avoid the same fate.

Three years ago today, I called an all-hands meeting to share the news with my entire team – CompleteSet was ceasing operations after being unable to secure additional capital. The meeting was brief, but it felt like it lasted for hours. I held back tears as I shared my mostly prepared remarks. The feeling in the room that afternoon matched the cold, grey sky of January in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Shock. Disappointment. Sadness.

That final all-hands meeting came after I had made the difficult decision to stop what I had started. January 12, 2018 remains one of the hardest days of my life. Despite raising $2.1 million in venture capital, graduating from the prestigious Techstars startup accelerator, growing revenue 40% month-over-over for multiple quarters, and building a talented team that served users in 45 countries, the company I had cofounded five years earlier still failed.

I felt like I had failed, too.

After an evening commiserating the outcome over drinks at the nearby Hotel Covington with a team that I loved to lead, we went our separate ways. The next day, I would begin the painful, months-long process of winding down the company. I would do so on my own while job hunting and coming to terms with the failure that we had all worked so tirelessly to prevent.

Although I made a brief Facebook post about the news and spoke about the experience publicly just a few months later, I never wrote a true post-mortem for the company. I could not muster the energy for it. For that reason, the exact cause for the company's failure and the fate of its products remained somewhat of a mystery to people other than our investors and the local startup ecosystem.

CompleteSet was the intersection of my professional experience building Internet products and my personal interest in collectibles. It was also supposed to be a venture-backed success story for the Midwest to celebrate. In this long-overdue essay, I will share the vision for CompleteSet that we were never able to fully realize and the primary causes of its failure.

The Vision

In late 2011, I noticed a trend in which collectors of all sorts of memorabilia were migrating from antiquated message boards to the more mobile-friendly Facebook Groups. In the process, fans began using the social network to upload photos of their collections, share what they wanted to buy or sell, and ask questions about the history of specific items.

As a member of these online communities, I thought this audience would be better served by a product built specifically for collectors. And as someone with web development experience and an entrepreneurial spirit , I thought I should be the one build it. In my view, neither eBay or Facebook fully served the needs of collectors. I also found there was no equivalent to Wikipedia that documented the history of collectibles to the extent that I thought was necessary.

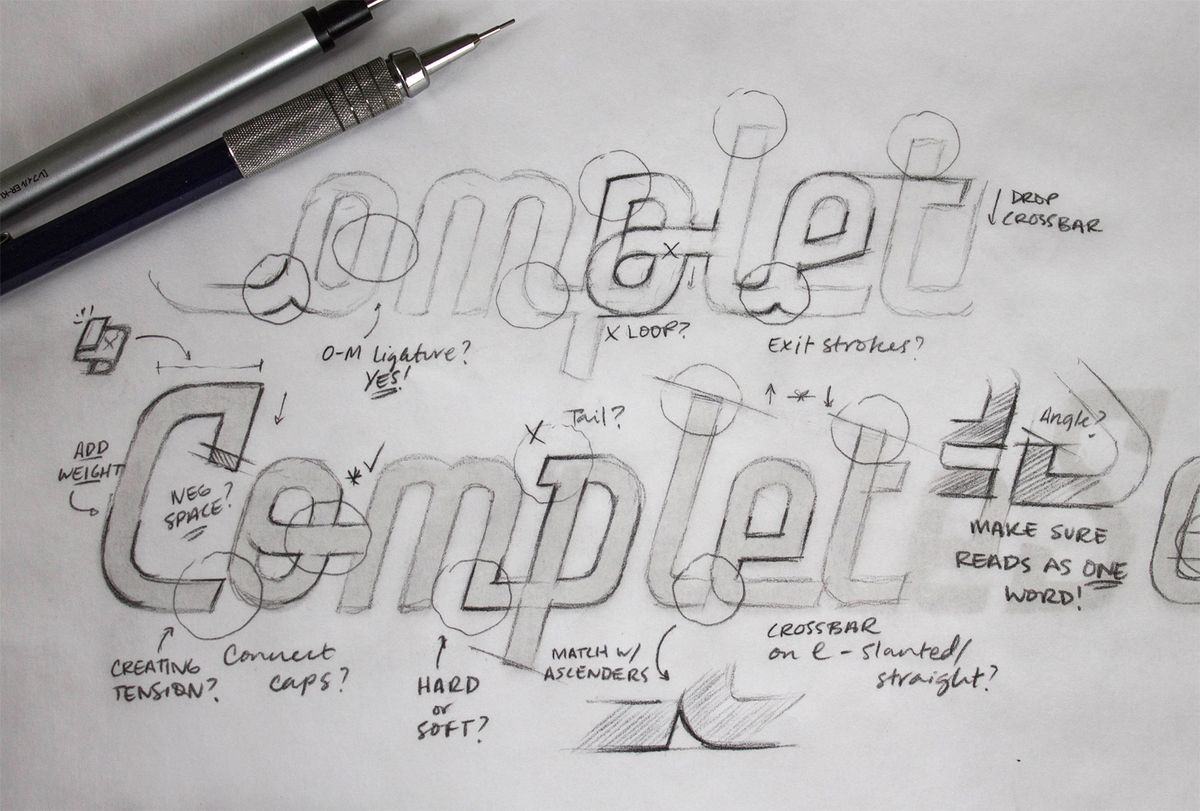

So that October, I created a mockup of what a web application for tracking collectibles would look like. Inspired by the pages of printed price guides that predated my app idea by more than a decade, I envisioned CompleteSet as the most comprehensive repository of information about collectible products ever offered. Each product would have its own page with attributes such as its name, manufacturer, release date, original price, country of origin, and photos.

To gauge interest, I cobbled together a simple landing page with a form to collect email addresses. To my surprise, nearly 1,000 people requested an invite to join in just a few weeks. The problem was, I didn't have a product yet. Although I had developed static websites and knew some basic JavaScript, I could not program an entire user-based web application on my own. I was stuck, but I did not stop.

For the next six months, I would attend every networking event that I could searching for a technical cofounder. The first time that I pitched CompleteSet was at a Startup Weekend event in January 2012, but no one joined my team. I had nearly given up when I heard that my alma mater had started a program to help students and alumni validate business ideas. If accepted to the program, I would receive mentorship, a $4,000 grant, and help recruiting a cofounder.

After an application and interview, I was accepted to The INKUBATOR in March 2012. Within a month, I had met my cofounder. Jaime Rump, a 19-year-old sophomore at the time, was less experienced than I had hoped, but he was eager to learn. We spent that spring and summer building a beta version of CompleteSet. I designed the user interface and wrote most of the front-end code, then sent over the files to Jaime so he could wire it up to a PHP backend and MySQL database.

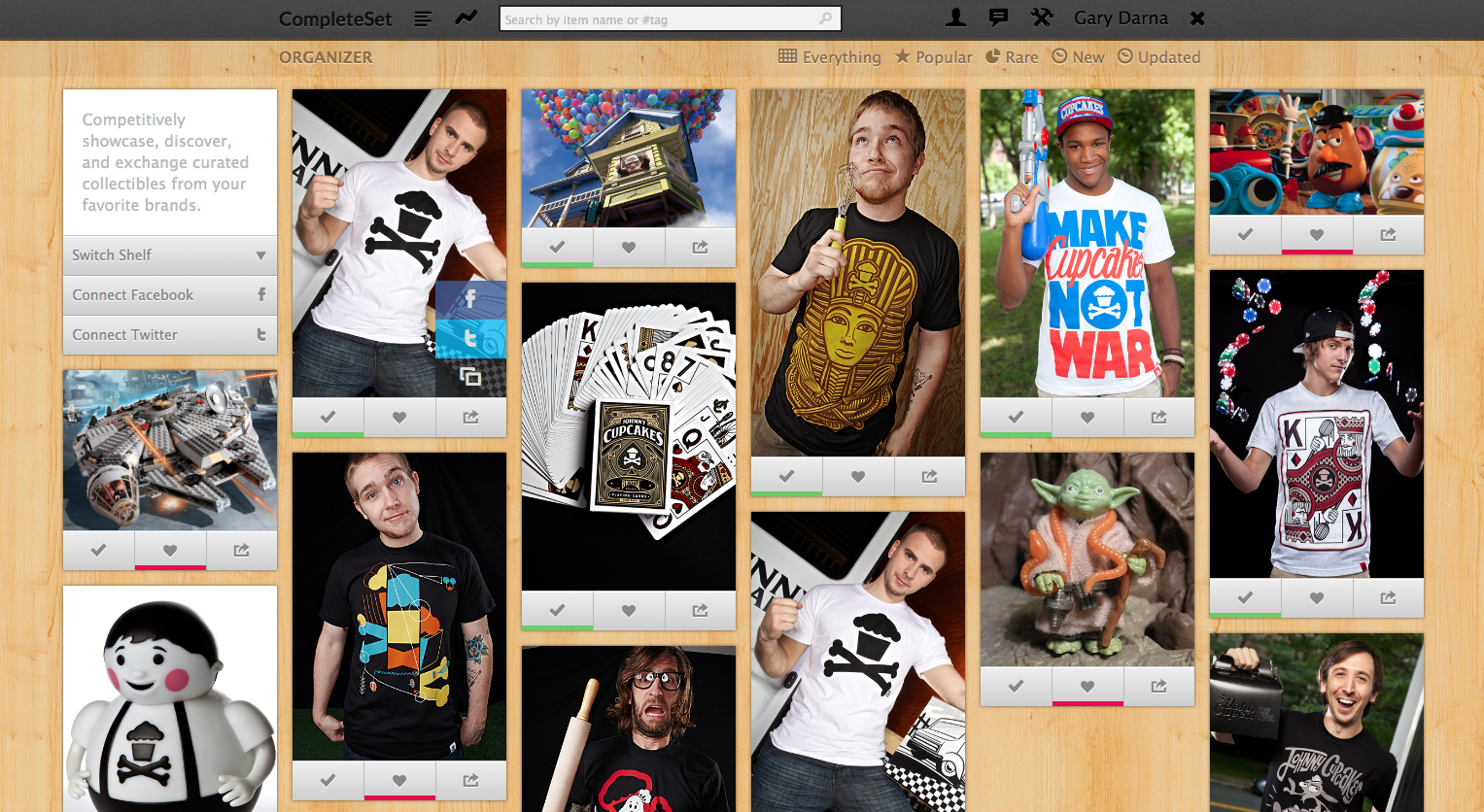

It took nearly a year from concept to launch, but in September 2012 we quietly introduced CompleteSet.com to the world. The reviews were mixed. While most users were excited to see it live, the product was slow, buggy and lacked a lot of content it needed to be a truly useful experience for collectors. We took that feedback in stride and kept iterating. Our efforts helped us win a $10,000 grant from CincyTech which kept us going.

Over the next two years, we developed the website on our own without compensation or assurance that it would succeed. Jaime wrote code in between his undergraduate classes. I worked on it seemingly every waking hour, talking to users and adding data. Through sheer willpower or stubbornness, we were able to sustain and grow our collector-centric website to ~5,000 users by 2014. This early traction helped us get accepted to a regional startup accelerator that year.

During the months between our launch in September 2012 and acceptance to the startup accelerator in April 2014, I tried to raise capital for CompleteSet to no avail. In hindsight, this was mostly because I had no idea how to raise money for a startup. We had some early signs of life, but didn't know how to turn it into a viable business. This was my motivation for applying to startup accelerators – to expand my network, learn from people who had done this before, and raise money.

Our luck began to change that summer. Through the accelerator's mentorship program, I met a retired entrepreneur and angel investor who had cofounded a venture capital firm. I scheduled the meeting to seek advice on how to raise venture capital, but during our conversation this mentor told me that he was interested in investing. It was not long after that we received a term sheet. We closed an oversubscribed seed round of $650,000 on November 22, 2014.

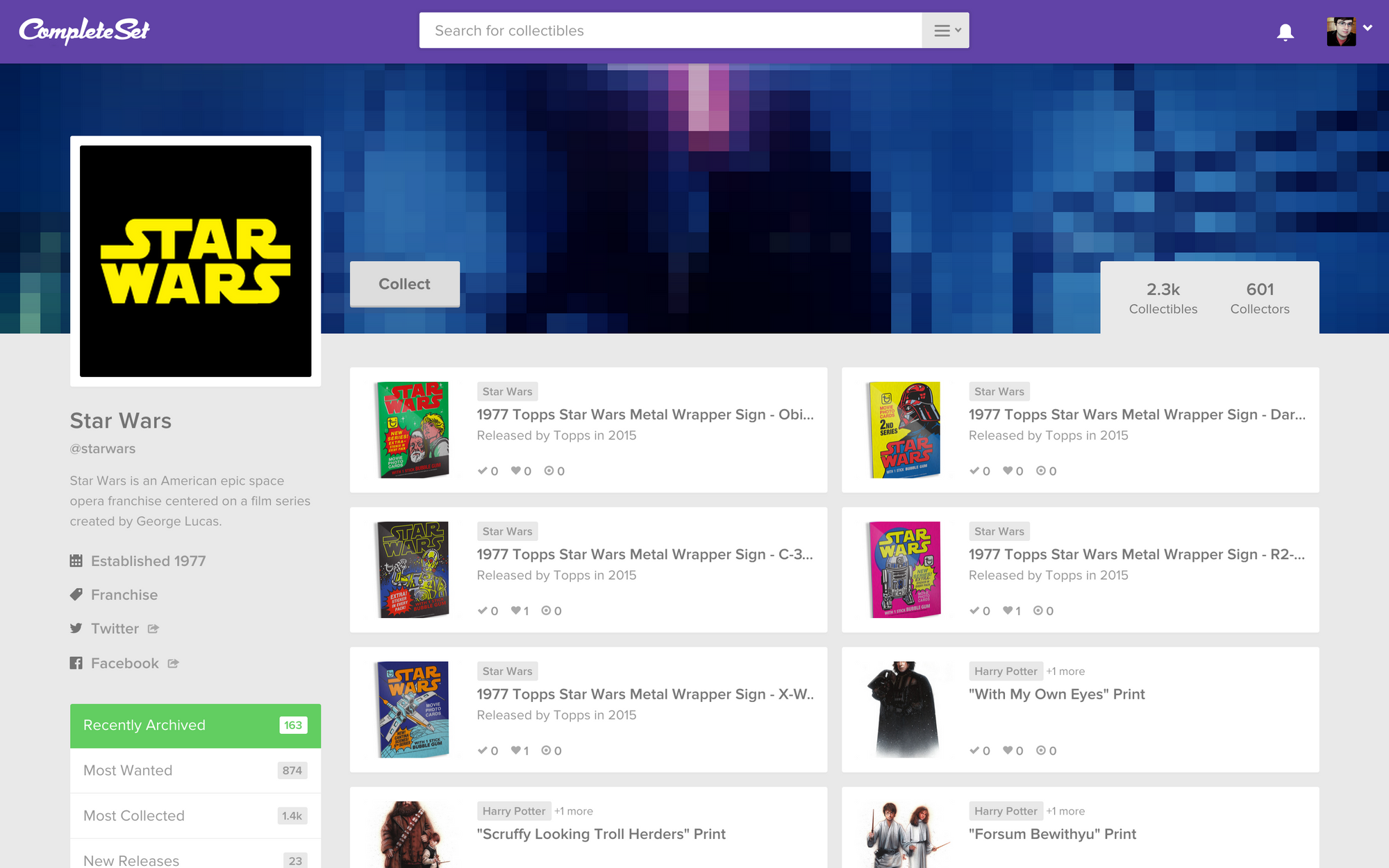

I felt a sense of relief in late 2014. We had turned an idea into a product, raised some money, and were off to the races. We went on to raise an additional $1.5M in two more rounds of funding. But contrary to what TechCrunch will have you believe, raising capital is not a milestone; it's an obligation. As the soon as funds were wired to our bank account, the clock was ticking. With each additional dollar raised, expectations only increased and it was our job to live up to them.

The Outcome

In hindsight, it felt like we were doing most things right at the time. We moved fast. We were capital efficient. We talked to users. We were accepted to one of the most prominent startup programs in the nation, Techstars, in 2016. We hired smart, talented people. We focused on growth. If there was an instructional manual for startups, we were following it. Little did I know that many of the decisions we were making would seal our fate as yet another failed startup.

As I shared during a presentation at the Hamilton County Business Center (HCDC) in 2018, CompleteSet suffered death by a thousand cuts. But if there is one reason for its failure, it's because we ran out of money. And as the startup's CEO, that's on me. Then as now, I believe a company running out of money is the effect of other causes – some more obvious than others. Since dissolving the company in 2018, I've reflected on the outcome to avoid making these mistakes ever again.

Hired Fast, Fired Slow

One of the many preventable errors we made as a funded startup was hiring too quickly. In fact, we hired our first employee within a month of closing our seed round! While this may seem like cause for celebration, the first hire I made was not the right fit for multiple reasons. Instead of offering a higher base salary to recruit the best talent, as the CEO I tried to conserve capital by recruiting less experienced people as our early employees. That was a mistake.

My hiring missteps didn't stop at starting salaries. Our first employee was a junior software engineer when it should have been a Head of Product. I've explained why previously, but in short, this person would have helped us implement a product-led approach to our business before we began adding features and scaling. Instead of assuming we knew what to build to grow the company, we should have invested every hour into reaching the elusive product/market fit.

A lot of startups hire fast and fire slow, so it's not surprising we made the same rookie mistake. During the five years that we operated, CompleteSet employed nearly two dozen people. The majority of our team were fantastic additions that made a positive impact, but some did not work out for a variety of reasons. Making a bad hire is not entirely avoidable, but it can be reduced by implementing the right hiring processes and incentives to attract the highest caliber people.

That said, continuing to employ anyone who demonstrates that they're unable or unwilling to fulfill the responsibilities of their role is a clear mistake. Yet it's something I did more than once due to my own inexperience and fear of handling the situation sooner. Even one bad hire can be damaging to a startup, and the situation doesn't improve as you scale either. Zappos' late founder Tony Hsieh once estimated that bad hires cost the company over $100 million.

The lesson I learned is this: You won't regret firing someone, but you will regret waiting too long.

Undercapitalized

When I started raising our first round of funding in 2014, I actually thought that $250,000 would be sufficient capital. I eventually came to my senses and increased our target amount to $500,000 (which ended up being $650,000 when we closed the round). Despite raising over $2 million in the company's lifetime, it was far from enough to build a successful online marketplace. I set us up for failure on day one by unknowingly undercapitalizing the company.

In retrospect, this happened for several reasons. First, I spent entirely too much time in one city when I first started fundraising. At the time, there were fewer sources of capital for seed stage companies in the region. Rather than expanding my network to connect with investors elsewhere that had experience funding B2C online marketplaces, I assumed that we could raise all of the capital we needed in Cincinnati. This was a critical error on my part.

Second, I did not understand financial modeling well enough to forecast how much capital we really needed. It's impossible to perfectly predict a company's financial performance especially in the early stages, but it's crucial to approach financing in terms of milestones. To do this well requires understanding what the next group of investors will expect to see. In our case, our seed round should have been large enough to put us on track to ~$100K/month net revenue.

Lastly, I also wrongly assumed that venture capital was the only option to fund the company. Like many young entrepreneurs, the allure of raising boatloads of money and seeing the company's name in the press distracted me from building a real business that generated revenue from day one. While it is true that many consumer apps delay monetizing their product in favor of growth, it is also true that less than 0.05% of startups are funded by venture capital.

Output Over Outcome

From the first website we launched to the multiplatform version that was live when we ceased operations, CompleteSet was a series of experiments. We tested just about every idea we could conceive of. From new features to user interface changes to variations of our business model, we continually tried new things. The problem with these ad hoc experiments was not how many of them didn't perform as expected, but how random and uncontrolled they were.

Although I remain proud of how quickly we iterated CompleteSet based on real user feedback, I'm disappointed in how little we relied on data for many of our most important decisions. I knew this was a problem at the time, but the push to move fast and build things was a constant tension. I recall attempting to expand our measurement beyond Google Analytics to something more robust like Mixpanel, but at ~$700 per month I thought it was too expensive.

Instead, we designed products largely based on qualitative feedback, intuition, and what little high-level data we had. We incorrectly implemented the objectives and key results goal-setting framework – and later stopped entirely. We added and removed features without extensive analysis, such as design sprints. We never ran a single A/B test. We built and released a lot of features, but without a product manager on our team, most were never optimized.

We valued output over outcomes, and it cost us.

Negative Unit Economics

Contrary to popular belief, many collectibles don't hold much monetary value. You will often hear stories of collectibles such as rare vintage action figures that sell for record-breaking prices, but these are the exception and not the norm. We learned this the hard way by attempting to build an online marketplace for collectibles of all kinds, from comic books to video games to porcelain figurines. If someone could collect it, we wanted it bought and sold on CompleteSet.

The challenge was how little some of these items would sell for. Consider one of the most most popular brands we featured on our website, Funko Pop. These 3.75" vinyl figures sell for about $10 at most retailers. Some of the rare Funko Pop figures can sell for hundreds or even thousands of dollars (yes, really), but by and large the average price point for these collectibles is much lower. Collectors may love them, but they won't support a venture-scale marketplace on their own.

For example, with a 10% transaction fee and average sale price of $15 for the typical Funko Pop figure, we'd need to sell over 66K of these things every month to reach the $100K in net revenue Series A investors expected at the time. Another popular category on our marketplace was Johnny Cupcakes t-shirts. Charging the same 10% transaction fee, but with an average sale price of $25, we'd still need 40K t-shirts sold through our marketplace to reach $100K per month.

To overcome this challenge and grow the supply side of our marketplace, we decided to launch an online consignment service. We would photograph, list, store, pack, and ship orders on the behalf of sellers. This transformed our peer-to-peer marketplace into a managed marketplace, which investors questioned for good reason. Instead of simply facilitating a transaction between two people, we now had to oversee the logistics of receiving, processing, and fulfilling orders.

Although the consignment service proved popular and propelled our revenue to 40% month-over-month growth, it also dramatically increased our costs. In effect, transitioning to a managed marketplace solved one problem but created many more. The most pressing of them was the existential threat of negative unit economics. For every listing we created, we incurred a ~$2 loss. By the time we realized how long it would take to improve these numbers, it was too late.

Had I relied on the financial modeling skills I learned from Troy Henikoff during Techstars, I would have made better business decisions. Troy taught us to always start from scratch with a new model, something I did not have before deciding to launch a managed marketplace. This exercise, while tedious, forces the founder to deeply understand their business model down to the unit economics of each sale. I was so focused on top line growth, that I overlooked the most important detail.

Three years ago today, the company I cofounded failed. CompleteSet ran out of money due to costly and mostly avoidable mistakes that many startups make. If we had approached hiring and fundraising differently, valued outcomes over output, and used financial modeling earlier to inform business model decisions then our story may have had a better ending. Founders, heed these warnings.

As my openness shows, I've never been ashamed of the outcome. I know that we executed with thoughtfulness, urgency and passion. I'm forever grateful for my cofounder, investors, employees, and our users for helping me turn my vision into a reality – even if only briefly. When I spoke to my team on this day three years ago, I promised them that their effort would never be forgotten. And I meant it.